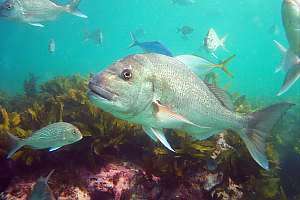

| Created as a place for scientific study, the reserve has inspired its many visitors. Being able to swim amongst thousands of friendly fishes, has first created awareness, then awe, followed by support for saving the sea. (on this page) | ||

| When the marine reserve was opened, education was never mentioned as a potential benefit. However, over time, as the environment around Auckland degraded further, schools chose to travel for two hours to find a place with marine life and clear water. | ||

| Feeding the fishes became the most popular activity inside the marine reserve, and reached problematic proportions. But stopping it altogether, created other problems. | ||

| Choosing the right size and shape of any marine reserve is critical to its later success. There are important lessons to be learnt. | ||

| To cater for the increased amount of traffic to the beach, the Goat Island Road was upgraded, causing masses of mud to enter the marine reserve - yet nobody took action. Why? | ||

| The land forms an integral part with the sea, particularly where run-off is dominant. The steep agricultural land around the reserve has suddenly begun eroding, with devastating effects. | ||

| When a marine reserve is successful, the fish stocks inside build up to the extent that they become hard to resist for poachers. It just pays to fish inside. Read the story of the sunken car wrecks. | ||

| Local and visiting users are the best agents for policing the marine reserve but it can be annoying. | ||

| Amenities like parking, rubbish containers and toilets become more urgent as the reserve attracts more people. Marking the sea with buoys, moorings and markers is necessary. | ||

| The marine reserve protects scientific experiments, allowing scientists undisturbed study of the sea but recently, research became more and more politically focused. Monitoring is important for any marine reserve but it should focus on all species and whether the reserve's objectives are being met. | ||

| When doing scientific experiments, it is often necessary to erect experimental structures on the shore or underwater, like cages, tiles, cables and so on. These structures have been left to rot, while leaving harmful obstacles for the visiting public. | ||

| It could be argued that a marine reserve could run itself, but wherever people congregate, some form of management is needed. The centrally led management of the Goat Island reserve has shown that it leaves much to be desired. | ||

| Concessions are not used yet but should they be introduced? | ||

| A glass bottom boat has become a popular way to experience the marine reserve, particularly for those unable to go into the water. Many consider it an excellent idea, but it interferes with the pleasures of others. What should one do? | ||

| The Marine Laboratory of the University of Auckland is not contented teaching university level science, and now plans to open an outreach centre for the public. Madness? "The planned Edith Winstone Blackwell Interpretive Centre will provide a facility for these visitors and also outreach programmes for primary and secondary school students, including local and Maori educational programmes." | ||

|

related pages

on this web site |

|

The Goat Island marine reserve in Leigh had a long gestation period, because

it was the first of its kind in New Zealand. Marine reserves have always

been an option in the Fisheries Act, but as conservationists became wary

of fisheries management, a new act was crafted, the Marine Reserves Act

1971 (MRA71). When the Department of Conservation

(DoC) was formed after the neoliberal 'Rogernomics' governments took hold

in 1984, it was given the responsibility to administer the MRA. |

The Goat Island marine reserve was effectively New Zealand's first, and nobody could predict how it would develop further and how many more reserves would be needed. Remember that the Marine Reserves Act 1971 (MRA71) specifies clearly that the sole purpose of marine reserves is that of scientific research. By 1996, this Act was revised considerably, to include more reasons for having them, reflecting the change in thinking (MRA96). Internationally, marine reserves were increasingly seen as a tool for saving the marine environment in the face of failing fisheries management. The word insurance was often touted. Scientists from New Zealand and elsewhere travelled around the world to broadcast the success of the Goat Island marine reserve, using it as a success story, and this is how people overseas know it, as the failures of the reserve were kept secret.

Indeed, the public rated the reserve successful. After about ten years of a luke-warm reception, visitor numbers suddenly started to increase since about 1988, as people learned to enjoy the sea without a need of catching fish. It changed their attitudes, finding out that fish can be enjoyed more intensively in a non-extractive, and completely sustainable way. But it happened by feeding the fish, which became tame and numerous because of this. The clusters of fish taking food from visitors attracted other fish which were attracted by safety in numbers. The number of visitors at one stage rose above 140,000 per year. People arrived in bus loads to feed the blue maomao and snapper in a channel off Hormosira Flats.

Originally attracted by the thrill of feeding the fishes, people could

not avoid reading the information displays about marine life and marine

conservation. It taught people more about the underwater environment. Schools

began to include marine reserves in their curricula using the very biased

information provided by the Department of Conservation..

|

|

To the casual visitor at least, the marine reserve looked successful

as evidenced by the many fish close to the beach. Scientists also measured

an increase in fish numbers, which they took as proof that marine reserves

are working. However, in this chapter, some of the more unsuccessful (and

often invisible) aspects of the marine reserve will be shown by someone

who has lived here since the beginning of this marine reserve, while making

frequent dives with movie and still cameras, and training students in its

waters.

|

|

|

|

EducationThe popularity of Goat Island extended to schools who came from far afield to find marine life and clear water. In 1992 the Seafriends Marine Conservation and Education Centre opened its doors as the first place in New Zealand to educate the public about the marine environment and conservation. Over 3000 students each year come here to study the rocky shore, experience a snorkeldive with full protective gear, and hear lectures about the sea. The Seafriends seawater aquariums show them the marine life from nearby. Without the vicinity of a marine reserve, such activities would have been hard to imagine. |

The school visits also made visible the damage done by people to the sensitive reefs in the intertidal zone. Towards the end of each season, there is just less to see. People also removed shells and other sea artifacts from above the high tide, which is perfectly legal. However, the rules had to be sharpened such that no natural object should be removed from the beach. We also pioneered the initiative to visit the rocky reefs on bare foot only. This has shown to be much less damaging to shore life like limpets.

Seafriends has also sharpened safety issues while taking groups in the water. Unfortunately many schools still arrive with inadequate gear and safety procedures. It must be noted here that schools think that safety is promoted by having more parents in the water, but this is not true. Safety is entirely dependent on the right equipment (full wetsuits) and an intimate knowledge of local conditions. More parents in the water just causes new problems, as most are inadequate swimmers, and inexperienced in this pursuit and the local conditions.

Seafriends has learnt over time, that it is more important to convey a sense of amazement and enthusiasm for matters of the sea, rather than scholarly facts. We work with enthusiastic professionals who have a heart for their work. Education outside the classroom (EOTC) requires students to listen to others than school teachers.

Whereas people do cause physical damage to the rocky shore by treading,

they cannot do much damage once they are swimming in the water. This is

because the water carries their weight entirely. Because water is about

800 times denser than air, storm waves cause far more damage than people

can ever do. Large numbers of people in the water can thus be supported

sustainably.

|

|

|

|

|

Problems with fish feedingFeeding the friendly fishes became the most popular pastime of a visit to Goat Island. Visitors asked "Where can I feed the fishes?" rather than "Where is the marine reserve?". People had fun creating feeding frenzies, placing food inside their dive masks, or holding food between their lips. Of course accidents were reported, such as torn lips, ears and fingers. Also during the height of the season, the water close to the beach became murkier, supposedly because of decaying food. Read the article To feed or not? for more details. |

But worse came after a junior official with the Department of Conservation prohibited the fish feeding altogether, without consulting the local community. Feeding was declared unnatural, unhealthy and an offence punishable under the MRA. First people ignored the ruling, while others removed the signs. When people were stopped entering the water with food, they resorted to breaking the sea urchins, which the fish loved even more than human food. People did so, even while knowing that heavy penalties were due for such offences.

It did not take long for the fish to realise that staying near the beach made no economic sense, and they disappeared in droves, and with them those fish that came for safety in numbers. Soon people noticed the disappearance of fish, and they stayed away too. Local businesses noticed the loss of income. For instance, Seafriends lost over $30,000 in each of the years following the feeding ban. It seriously hampered our efforts in saving the sea. For their first visit to a marine reserve, children were no longer seeing fish nearby and in large numbers. On many snorkel trips out, some saw no fish at all during a 50 minute swim !!

The people who manage this reserve, seldom or never are in the water, and they have but a rudimentary understanding of marine matters. They were unaware that since 1990, the ingress of mud into the reserve, had become the largest threat. Mud flows from the denuded and degrading land surrounding the reserve, and from the Pakiri River further west. It has suffocated and killed underwater life, and driven entire species out of the marine reserve, while also changing habitat structure. In June-Sept 1998 this problem became so pressing that nearly all crayfish walked out of the reserve. The friendly fishes thus experience a stress to move away from the beach, whereas the feeding attracted them in. Those species that cannot move easily, either died or stayed away. Now that the balance had shifted, the fish stayed away.

What was infuriating about DoC's decision, was that the problem was

not in the feeding itself, but in the quantity fed during a limited period

of the year. This problem could easily have been turned into a learning

opportunity, by explaining it to the public, giving various alternative

solutions, and letting them do what suits them best, while taking responsibility

for their actions. Now that far fewer people are visiting the reserve,

also an opportunity for education has evaporated.

The following rules could have been applied: Only

close to the beach. Only a handful per person. Never on SCUBA. Never sea

urchins. Don't buy food. Give some of your own lunch pack. Children only.

Another missed opportunity was that of losing support for marine reserves.

Not DoC, nor University, nor Government in the end were as effective in

broadcasting the conservation message, as were the blue and pink fish that

people came to feed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Size, shape and locationThe Goat Island marine reserve was the first of its kind and it is understandable that its boundaries could be improved upon. At the time the rocky shore habitat was seen as its most important part, containing most of its species diversity and inviting most of the scientific experiments. It was thought that a ribbon of 800m width would be all that was necessary to protect this habitat. |

But for the same reasons, it cannot serve as a baseline to compare 'outside' coasts with. However, scientists seldom make such distinction in their publications about the benefits of marine reserves.

The marine reserve is 5km long and 800m wide, but because it curves around Goat Island, its area is effectively 5.2km2, which is too small to be sustainable. A sustainable reserve is thought to be able to exist by itself without the need of the area around, while also not being drained by it. It needs to be sufficiently large to do so. However, even then it is still dependent on the amount and quality of the plankton imported from other areas. It is now thought that 'sustainable' marine reserves should be as large as 100km2 rather than 5km2. A reserve is sustainable only if it does not degrade. However, Goat Island has shown to be degrading fast.

It was insufficiently recognised at the time, that the seemingly monotonous sandy bottom was important for reef fishes and rocklobsters. On a regular basis, these animals migrate to their 'feeding grounds' of dog cockles, horse mussels, dosinia and scallops far outside the reserve's boundary. At the time this reserve was created, it was not realised that opposition came from those who fished the shore rather than those who fished the seabed. Extending the reserve another 5km out to sea, would have met little additional opposition but would have added considerable conservation value.

Another major mistake was the choice of the coastal boundaries, which now run across continuous rocky habitat. It was not predicted that the reserve's boundaries would invite an unusual amount of fishing. Thus the boundaries are depleted by fishing but replenished by reef fish moving out of the reserve into vacated territories. Had the boundaries been located outside a change in habitat, such as over the nearby sandy beach, such leakage would have been minimal and correspondingly the harmful effect of 'fishing the line'.

One of the most serious deficiencies of small reserves is that they leave no room for buffer zones which buffer the effects of fishing and mistakes made by not knowing precisely where boundaries run. It must also be recognised that seamen do not measure distance in kilometres or land miles but in nautical miles. Reserve boundaries should thus be defined in nautical miles.

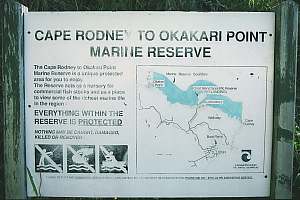

Perhaps trivial, the name of a marine reserve must be simple and easy to remember. Cape Rodney to Okakari Point marine reserve is wrong because nobody uses it. Leigh marine reserve or better still, Goat Island marine reserve are much better names. Many of the (Maori) names for marine reserves in NZ are just too long and cumbersome.

Marine reserves are usually created in marine hot spots where the water

is clear and fish congregate. But these qualities make them unsuitable

for baseline studies, for example to compare more normal

areas with, when studying the (beneficial) effects of marine reserves.

Such hot spot marine reserves exaggerate the perceived benefits. However,

scientists do not sufficiently acknowledge this.

|

The area around the outside of Goat Island is a marine hot spot in the clearest and deepest water, near currents and feeding grounds, while offering shelter against waves. Yet scientists do not acknowledge this. |

|

The Goat Island RoadThe Goat Island Road leads from the main coastal route through the Goat Island valley (Whakatuwhenua Stream) to the Goat Island beach and the Marine Laboratory. Its climbing and winding part has been tar sealed in the early 1980s but its gently sloping lower part remained unsealed in gravel or 'metal' as it is called in New Zealand. |

We ask ourselves why nobody took action to remedy what was obviously a major threat to the marine life inside a protected area.

|

|

|

|

|

Coastal erosionCoastal erosion is a sad story all over New Zealand but particularly where the coast has been burnt for grazing. The coasts bordering the Goat Island marine reserve unfortunately form no exception. Where the coastal forest descended almost into the sea, farmers saw an opportunity of grazing it. As a result, the coastal fringe was burnt wherever grass could be established. The 50-150 years of grazing left its ecological footprint on this coastal strip through the absence of seedlings and young trees that should take the place of their parents now that these are dying from old age. |

|

|

f960507: during storms the mud collected on the sea bottom is stirred up, clouding the waters. f212406: Heavy rain storms now colour the water brown as it runs off from degrading lands surrounding the reserve and the Pakiri River located west of it. |

|

Where coasts are steep and farmers did not take the torch to the trees, the vegetation is under attack of a little monster introduced from Australia where it has in the meantime become endangered. The possum (as opposed to the American opossum), a marsupial, lives its entire life in the trees, descending only to make long journeys to other trees. In its pouch, a mother possum rears one joey which grows independent within one year. As a result, the fecundity of this species is high.

One would think that trees are productive enough to survive the possum's

grazing, but this is not the case in New Zealand, where the vegetation

has developed very frugally. Thus contrary to expectation, native trees

do not survive the grazing of possums, which has resulted in entire coasts

being denuded. Now one can see the yellow bands of eroding soil where once

trees stood but even this will eventually become invisible. In the end

it will seem that New Zealand has always had denuded coasts.

|

|

Then DoC applied a possum poison (1080?). Now the island remains quiet by day and night. Fighting the possum plague is not easy. |

|

|

PoachingDepending on how intensively the sea outside has been fished, the stocks of fished species inside a marine reserve will recover, usually by 2-3 times but sometimes more. It means that fishing inside becomes very rewarding. As the word goes out, often exaggerating about the bounties inside, it tempts people to poach. |

In the beginning of any marine reserve, poaching is frequent because of those who oppose the reserve but mainly because people have to get used to the new situation. Often a word is enough to stop it altogether. In Leigh even the most ardent poachers have given up under the pressure of derision by their mates. But there is a good story to be told.

The sunken car wrecks

A marine reserve is particularly unfair to those fishermen who depended

on the area for fishing. One would think that the sea is an open access

fishery but this is not so in practice. Commercial fishermen have unwritten

agreements on who fishes where, and so it can happen that the burden of

displacement falls on only a very few.

Once the marine reserve becomes a fact, the only place to fish is on

its boundaries, which explains why fishing there is often done by those

displaced. The seaward boundary of the reserve runs into a flat sandy bottom

with good stocks of burrowed clams, fan shells and a scallop here and there.

It is a fishing ground for fish, or a feeding ground. Snapper make daily

migrations out of the reserve to visit such feeding grounds and even rocklobsters

do so. They even stay on the sand, forming aggregations guarded by large

males. In this manner the rocklobster fishery on the Chatham Islands rose

to fame, where fishermen caught these crayfish with trawl nets!

But trawling is prohibited closer than 0.5 nautical miles in winter

and 1.0nm in summer. By comparison, the boundary of the reserve lies within

800m or 0.468nm. An error of judgement is easily made of course, particularly

since the outside boundary is not marked. So one trawler of a big fishing

company did the dirty and trawled its net through the reserve by night,

to bag 500kg of crayfish or a cashie as it is known, fetching $20/kg

on the black market. This was a $10,000 windfall profit for the crew, worthy

of imitation and so it happened.

However, in the process, these trawlers also scooped up the precious lobster traps (craypots) which annoyed the local cray fisherman no end. He complained, but received good laughter. Then he conceived a clever plan. He parked a number of car wrecks on the Leigh wharf, and by means of a strong tether, swooped them off the wharf deck into the sea, where he trawled them to within GPS precision inside the reserve's boundary. Several more car wrecks followed and the news was broadcast.

It had the expected effect and protected his cray pots. However, a Leigh trawler ended up stuck in a car wreck (oops) and began to complain to the Maritime Safety Authority which then began to lean heavily on the poor fisherman. The situation had now become a SAFETY issue and the car wrecks had to go! So it happened. But the word remained that one was not quite sure whether all car wrecks had been retrieved!

The fisherman has in the meantime moved elsewhere and has not bothered

fishing the boundaries of the reserve since 1998 (when the crayfish disappeared?).

Poaching does not happen to marine reserves only. These crayfishermen complain

that about 10% of their catch is poached by others (divers and other fishermen).

|

PolicingPolicing to enforce the no-take rules is dreaded by all. The idea that rangers are policing the last bastion of freedom is anathema to boaties, divers and fishermen. These people wo ply the seas, are of a rugged type, hardened by the elements and are not easily impressed. Once they see the need for a marine reserve, they turn into the staunchest of supporters. But they will never stoop to the lowness of being a ranger. For this office more gullible and principled types are found, ready to dish out condescending remarks about 'offences' that do not really matter to the environment, while being terribly upset about minor issues. |

The problems in enforcing rules are as follows:

|

AmenitiesParkingParking and amenities are always a problem since their need cannot be predicted in advance and also because visitors do not arrive in a steady stream but mainly in the summer season when during a few weekends they are shown to be inadequate. |

The top parking consists of a loop, just wide enough for buses to turn and angle-park off it. Two tighter loops lead to two terraces lower down. When fully occupied, visitors park along the access road up to 1km away from the beach. During such days it is estimated that over 4000 people are present on the beach and that some 10,000 visit that day by rotation.

There are a number of issues to consider. In the good old days a gravel country road led to a grassy knoll which was the parking lot. Visitors met sheep grazing the grass as free grass mowers. A cattle stop grid prevented the sheep from straying out of the parking lot. Visitors used all kinds of inventivity to make best use of the available space, which was neither bordered nor marked. After the weekend, the parking reverted back to a grassy knoll as if the paddock had never been disturbed. Today a black tar sealed infrastructure remains when the people have left. It offers less parking for more space. What went wrong?

On wet days cars could get stuck in the mud pools that developed as

the reserve's success rose. The car park needed hardening. Locals would

have done so with a hardened structure that would let the grass through;

an urban bureaucracy chose for hard tar seal and rigid parkings with wooden

barriers to prevent cars from straying out. Why?

Suddenly it became an offence to park in a creative way. Suddenly there

were much fewer parkings. Was this necessary?

When the three-lane highway was completed, there was ample room to dedicate one lane to angle parking along up to 500m away. Instead, a small lane was marked, just enough for parallel parking. Fewer parks again.

Then the department did away with the sheep because trees were being

planted and it was more convenient to do away with the sheep and the cattle

grid rather than fencing the new trees. The cost of maintenance increased.

|

|

| Rubbish

Once there were rubbish bins for the convenience of the visitors but these required upkeep and were inadequate during a few very busy weekends. Now people take their rubbish home because the rubbish facilities were removed. Gradually people became used to the new regime and it appears to work. |

| Toilet facilities

Fresh running water is not available at Goat Island, and puritans of the enivronment somehow resist it. So people can't wash their feet clear from sand - not a problem because the grass will rub it off. As successful as the taking home policy is for rubbish, it can't work for ablutions. By the lower parking stands a small building with two equally small halves, for the separate sexes. There is a communal space each for changing and three toilets each for males and females. |

Not surprisingly, the Seafriends toilets about 1.5km up the road, bring welcome relief. One of three is dedicated to invalids and mothers and it is very much sought after with its running warm water.

Should a beach, however pristine have proper toilets with running water

and hygienic washing facilities?

Update

A

new toilet block has been built as shown on the photo. The problem of running

water was solved by a bore and the sewage is treated by a local sewage

treatment plant, left of the photo. Council workers clean the toilets every

morning. There are waste bins for recyclable and nonrecyclable rubbish,

yet the change has left a notable impression. A

new toilet block has been built as shown on the photo. The problem of running

water was solved by a bore and the sewage is treated by a local sewage

treatment plant, left of the photo. Council workers clean the toilets every

morning. There are waste bins for recyclable and nonrecyclable rubbish,

yet the change has left a notable impression.

Whereas previously the sewage was slurped up by a sewage truck and discharged in a proper place somewhere else, the present system eventually spills the processed water into the local creek and the marine reserve. As a result, the creek's water has become black and the water in front of the beach always murky. The new system leaves a small influence on the environment for every visitor, whereas the previous primitive system did not. As the reserve becomes more popular, the environment recedes proportionally. As usual, humans destroy the places they love. |

| Interpretation and kiosk

Coastal marine reserves are places where people arrive by car and then walk to the beach. The Goat Island marine reserve allows access to the water only in one place, by Goat Island. Thus everyone funnels through a narrow passage to the water. Here an information kiosk was placed with hand-painted displays of the marine environment and its inhabitants. Although most people walk just past, many study it carefully. |

|

"The Cape Rodney to Okakari Point Marine Reserve is a unique protected area for you to enjoy. The reserve acts as a nursery for commercial fish stocks and as a place to view some of the richest marine life in the region. EVERYTHING WITHIN THE RESERVE IS PROTECTED. NOTHING MAY BE CAUGHT, DAMAGED OR REMOVED." |

| Buoys, moorings and markers

It can be said that all the money in setting up and maintaining the marine reserve has been spent on amenities to benefit visitors. Nothing nice has been done for the marine environment. Divers have been left in the cold too. It concerns the use and maintenance of markers and buoys. |

Dive groups requested permission to restore these markers and to place more permanent moorings on their preferred training grounds over sandy areas at about 10m depth. Such moorings help reduce anchoring damage and they provide a focus for safety in case of emergency. But permission was denied. Why?

The marine reserve has sensitive benthic communities of sponges, also called sponge gardens. Although an anchor would not necessarily cause grievous damage, the anchor chain does when the wind or currents change and the boat swings around, the chain scraping the bottom. In such areas for the sake of protecting the sensitive habitat, strong moorings must be provided to signal that anchoring is prohibited and to provide an alternative. No such mooring buoys have been provided. Why?

The outer boundary of the marine reserve is almost impossible to locate, even with the proper equipment such as radar and GPS. Boundary markers should have been provided from the very beginning and maintained thereafter. This has not been done. Why?

Passengers can embark boats only off the small beach, and only where

no boulders are found. It is a very restricted area where also many swimmers

begin their discoveries. A collision between propellers and swimmers is

thinkable but even so, is not of real concern because everyone is attentive

and boats make only slow progress while people have also become used to

the situation. However, the only glassbottom boat operator now claims a

large proportion of this scarce resource, forcing others to wait or take

risks.

|

ScienceThe Leigh Marine Laboratory is located at the centre of the reserve, and indeed this reserve has specifically been created to allow scientists undisturbed access to the sea and protection of their experiments. But recently research has become more and more politically motivated. Mostly funded by the Department of Conservation who manages NZ's marine reserves, and whose interest it is to prove that marine reserves are working, research has focused on real and perceived benefits of marine reserves. |

Science has made civilisation great, and where supported by science, political decisions are better. While our use of the sea is intensifying at the same time that the degrading influence of the land is accelerating, research is needed to provide reliable knowledge for making long-lasting environmental decisions. Unfortunately, several things have gone wrong, as clearly set out in Myths(7) and Science Exposed, and also reflected in the long list of wrongs in the present politics regarding marine conservation. This is not the place for dwelling on the shortcomings on research done. Instead we'd like to stress the need for marine research wherever reserves are created. This research has the following nature:

|

|

|

Scientific pollutionAs part of their experiments, scientists often have to make changes to the environment, like mounting exclusion cages, settlement tiles and so on. All too often, however, these are not removed after the experiment finished. Some end up half destroyed by the sea, littering the places where they come to rest. Yet others remain a threat to visitors, such as steel bolts protruding from the rocky shore where school children wander. For a long time there have been clusters of cables littering the sea. |

|

|

|

ManagementMarine reserves in remote areas can practically be left unmanaged as long as some supervision against poaching is present. But closer to human populations, more management is needed. In the unlikely case of a clear-water marine reserve with easy access near a large city, people will arrive in droves, particularly on warm days in the summer holidays. |

The international literature on marine reserves unanimously agrees on

forms of local management with participation of stakeholders and local

administrators. Most people (landlubbers) insufficiently understand the

special nature of the sea and how it should be managed accordingly. Thus

one of the largest impediments to success is central management by an ideologically

motivated government department (DoC), as is the case for Goat Island.

These people are so far removed from the sea and a reserve's daily needs,

that management causes more conflict than it resolves. It is also less

cost-effective while the benefits from maintenance and support do not flow

into the local economy.

|

ConcessionsThe Department of Conservation is keen to introduce concessions in order to exert further control over the use of the marine reserve. A concession gives the right to conduct a certain activity. It provides an income for the maintenance of the reserve and is in the order of 10% of revenue or as much as 30-40% of gross profit. Operators add a concession fee to their fares and pay DoC accordingly. Such cash generating systems are now in use in National Parks but their value for the sea must be questioned. |

1) The sea is a domain with free access and concessions would interfere with this freedom.

2) The concession system is purported to enable DoC to control commercial activity in marine reserves, but we have coped well for 27 years so far, without any. It claims that non-commercial activity is free from concessions, but in many cases, it is exactly this which must be controlled for the sake of the environment. In other words, the concession system is not aimed at controlling activities detrimental to the environment, but aimed only at making money.

3) Since concessions are based on extracting money, (a large percentage of profit), DoC is effectively having a finger in the honeypot. This means that it can no longer be seen to be an independent and impartial manager. As is known from many examples, DoC will be tempted to judge in favour of the honey, rather than the environment. This is already becoming evident in whale and dolphin watching.

4) Concessions can and will be allocated to the highest bidder. This means that it favours large operators, to the detriment of smaller, often local operators. They, in turn, use it to keep competitors out. The local community suffers, as DoC creams off their potential profits. The commercial 'extraction' mushrooms as companies market their products aggressively in trying to maximise their profits. The environment suffers.

5) It is wrong to bring in a system that makes people who go about their

normal business, culpable or accountable to concessions. Dive operators

have been using marine reserves for training for as long as these exist,

indeed they have used the area long before. In fact, the Goat Island marine

reserve was somehow taken off them. They do not go there for seeing fishes,

but they use the shelter and clear waters around Goat Island for training

and tests. At the same time, they introduce novice divers to the marine

conservation concept. To drive them away, or to subject them to concessions

for the simple reason that they are 'commercial' is anathema to the freedom

every New Zealander is born with.

|

Glass bottom boatBecause they attract visitors, marine reserves also attract commercial activity such as glass bottom boats. Often these are encouraged by management in order to enhance the popularity of the marine reserve. However, over time, as the commercial enterprise grows, conflicts with other activities arise. The glass bottom boat is taken as an example but please note that the current operator is aware of possible conflicts and tries hard to avoid them. |

The early version of the glass bottom boat for which permission was given to operate inside the marine reserve, was a small tub that could seat some 20-30 people around a central window. It was small enough to take advantage of small beaches while hardly interfering with swimmers and snorkellers. Then suddenly a much larger model appeared, this time large enough to do a bus load of passengers at once. Passengers are now seated around two windows. Soon complaints from other beach users began to surface:

|

|

|

Outreach centreThe University of Auckland plans to establish a public "educational outreach centre" as part of extensions to the Leigh Marine Laboratory, now renamed the South Pacific Centre for Marine Studies (SPCMS). The new centre is "for visitors to the area and school children in Auckland and Northland to better understand the marine environment". However, this function has for 16 years been fulfilled by the Seafriends Marine Conservation and Education Centre located at the Goat Island Road, a mere 1km from the sea and the Marine Laboratory. So why would the New Zealand Government attempt to kill an established private institute with a long track record of excellence in marine education for the public?Read what the Marine Laboratory expansion entails and the questionable thinking behind it. |

|